Supporting Point Lights

This is finally going to be a more technical post. As the title suggests, I’m going to cover how the many lights algorithm supports point lights in Blender. I expect this to be a slightly lengthier post because I want record some insights I’ve discovered about Cycles, some details that Brecht and Lukas have explained to me, and some more details about the algorithm itself. Before reading this, I would highly recommend reading either my previous posts or the original paper.

Also, just as an update, it seems like Cycles has recently updated their device code and no longer refers to the device arrays as “textures” anymore. You’ll see what I mean if you read the section about transferring to device-side - just know that “data arrays” are now the equivalent of what I meant by “textures.”

Implementation

Before I get into the details of the implementation itself, I first want to go over some of what I’ve learned about Cycles. From what I understand, the device-side kernel has two main ways of keeping track of data. Both are stored in a struct called KernelGlobals. In this struct, it contains a member called __data, which in turn contains members such as the integrator that contains certain render settings and fixed constants. This takes up a fixed amount of memory and I imagine that it should be faster to access on the device. The struct also contains other data in the form of flat arrays. The amount of data that goes in here is dynamic, i.e. the lights in the scene. This is where we’ll also be adding new data such as the nodes of the light tree to traverse (more on that later).

When Cycles starts rendering, the logic goes through a megakernel that determines which functions to call next. For example, the first function to call may be integrator_intersect_closest() to find an intersection. That function can write things to some state for other functions to read later, and it can also schedule the next kernel task. For example, after finding an intersection with a surface, we may want to queue integrator_surface_direct_light() which will sample a light, and then in turn call integrator_intersect_shadow() to check the visibilty of that light.

Knowing this, there are essentially 3 main tasks:

- Using the scene information to construct the light tree on the host side,

- Transferring the light tree to access on the device side,

- Using the light tree to determine light sampling in the kernel.

Next, I’ll elaborate on how each task was implemented.

Host-side Construction

As I mentioned in an earlier post, the host-side construction of the light tree isn’t really anything notable. It follows PBRT very strictly, but we replace the surface area heuristic (SAH) with the surface area orientation heuristic. This is done by associating each light primitive and node with an additional bounding cone that keeps track of orientation and general emission direction. Here, we define a custom struct called OrientationBounds to keep track of this information:

// intern/cycles/scene/light_tree.h

struct OrientationBounds {

float3 axis; /* normal axis of the light */

float theta_o; /* angle bounding the normals */

float theta_e; /* angle bounding the light emissions */

}

The reason we have both \(\theta_o\) and \(\theta_e\) is for certain light sources, like a point light. Since there’s really no “orientation axis” for a point light, we can technically consider any direction to be the orientation and then bound the axis to be within \(\theta_o = \pi\) radians of that direction. Then the \(\theta_e\) describes the angle of light that will be directed in the orientation axis. Again for a point light, this covers an angle of \(\pi/2\) around the orientation axis, and any angle past that will be facing behind the axis.

When we merge two bounding cones, we find the centroid of the orientation axis, and then we compute new values for \(\theta_o\) and \(\theta_e\) that will bound that of the original two. This seems to be a generelly effective and safe approximation of the net bounding cone, but if I have time, I may consider somehow incorporating position data into this merge.

Transferring to Device-side

In my second post, I also discussed the sort of information that we need to access for traversal on the device side. I’ll explain why we need certain information in the next section, so this section is just focused on how we transform the information from the host-side into a flat array on the device side. We add have an array of this struct to be stored on the device:

// intern/cycles/kernel/types.h

typedef struct KernelLightTreeNode {

/* Bounding box. */

float bounding_box_min[3];

float bounding_box_max[3];

/* Bounding cone. */

float bounding_cone_axis[3];

float theta_o;

float theta_e;

/* Energy. */

float energy;

/* If this is 0 or less, we're at a leaf node

/* and the negative value indexes into the first child of the light array.

/* Otherwise, it's an index to the node's second child. */

int child_index;

union {

int num_prims; /* leaf nodes need to know the number of primitives stored. */

float energy_variance; /* interior nodes use the energy variance for the splitting heuristic. */

};

/* Padding. */

int pad1, pad2;

} KernelLightTreeNode;

static_assert_align(KernelLightTreeNode, 16);

In my previous post, I mentioned that we would use two separate structs to store interior and leaf nodes. However, as explained in the comments, we can use the child_index to determine whether or not a node is an interior or leaf node. Then the union is used to store the non-overlapping information. Other than that, we need the two extra pad1, pad2 ints at the bottom to pad our struct so that it aligns to 16 bytes.

Now we need to add an array of this struct to the DeviceScene. This is what we’ll actually be able to access through the kernels:

// intern\cycles\scene\scene.h

class DeviceScene {

public:

...

/* light tree */

device_vector<KernelLightTreeNode> light_tree_nodes;

...

}

// intern\cycles\scene\scene.cpp

DeviceScene::DeviceScene(Device *device)

: ...,

light_tree_nodes(device, "__light_tree_nodes", MEM_GLOBAL),

...,

{...}

The reason why we pass those parameters to initialize light_tree_nodes is because the device_vector uses this information when copying to the device. From my understanding, it’s kind of like an intermediary where we can fill in the device_vector from the host side, and then tell it to transfer that information to the device. In Cycles, arrays of data are stored as textures on the device, and the device_vector will look for a texture with the given name to populate. Ihis case, we passed in "__light_tree_nodes" as the name, so we need to make sure there’s an appropriate texture that corresponds to that name:

// intern\cycles\kernel\textures.h

...

/* light tree */

KERNEL_TEX(KernelLightTreeNode, __light_tree_nodes)

...

The last thing we need to do is populate the device_vector before we tell it to transfer its data to the device. Since PBRT’s BVH construction already flattens the tree, all we need to do is iterate through the packed array and create the device-side struct accordingly. Sounds easy, but before we even construct the BVH, we first need to obtain an array with all the light primitives to be included in our BVH. Since we’re only dealing with point lights for now, this isn’t very interesting (and this post is getting quite lengthy), so I’ll omit it for a later discussion when more types are supported. For now, just trust that we’ve successfully transferred our linearized BVH onto the device through the texture __light_tree_nodes.

Device-side Traversal

Now that our light tree is on the device, we can use it to take more informed samples. When we begin at the very top parent of the light tree, we need some way to decide which child we should traverse to, i.e. what the relative importance of each child is. Recalling the rendering equation, there’s 2 main terms to consider:

- The irradiance term, \(L_i(p, \omega_i)\);

- The BSDF term, \(f(p, \omega_i, \omega_o)\).

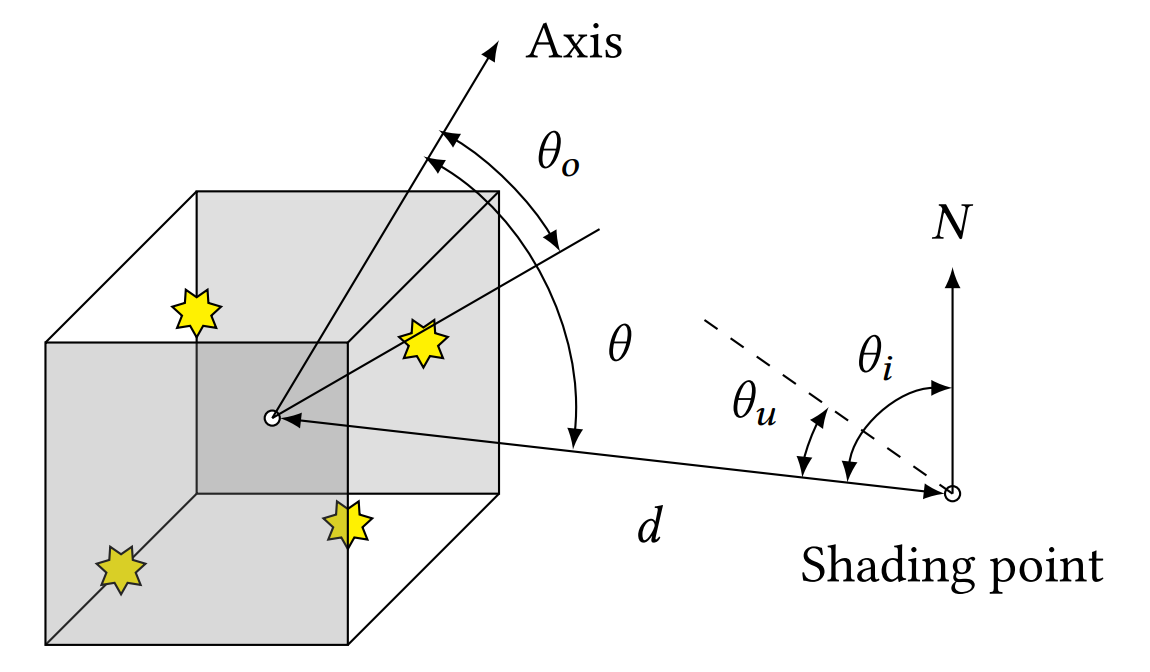

The importance of a node cluster should thus be an approximation of how much it relatively contributes to these terms. To do this, we want to loosely bound the range of possible values. This is the diagram that the original paper uses:

This is how the symbols are defined:

- \(\theta\) is the angle formed between the cluster’s bounding cone axis and the vector pointing from the centroid to the shading point,

- \(\theta_u\) is the max angle required to encompass the entire bounding box (around an vector pointing from the shading point to the centroid),

- \(\theta_i\) is the angle between the shading point normal and the centroid.

The paper then gives the importance measure as follows:

\[I = \frac{f \lvert \cos(\theta_i') \rvert}{d^2} \times \begin{cases} \cos(\theta') & \theta' < \theta_e, \\ 0 & \text{otherwise}. \end{cases}\]where \(\theta_i' = max\{\theta_i - \theta_u, 0\}\) and \(\theta' = max\{\theta - \theta_o - \theta_u, 0\}\). These are a lot of new terms, but hopefully you can see some loose similarities between this importance measure formula and the integrand in the rendering equation. This is my interpretation of \(\theta_i'\) and \(\theta'\):

- \(\theta_i'\) is the minimum angle that could possibly be formed between the shading point normal and a vector pointing from the shading point to a light in the cluster,

- \(\theta'\) is the minimum angle between the emitter normal and a vector pointing from a light in the cluster to the shading point.

These heuristics are all very loose bounds, but it’s still a decent approximation to determine the weight of sampling each cluster.

Writing all the code here would be pretty redundant because as of right now, it’s a pretty immediate mapping from math to code. If you want to look through it, it can be found at intern\cycles\kernel\light_tree.h. Most of the angles are either already given, or can be calculated by taking \(\cos^{-1}\) of the dot product between the two normalized vectors in question. The only somewhat notable calculation is \(\theta_u\) because there’s no easy way to know what minimum angle will encompass the entire bounding box. As such, we must iterate through each point of the bounding box to find the max angle formed (which will contain all the others).

Once we have the relative importance of each child, we assign the probability of traversing to the first and second child (this is also referred to as left and right in the code):

\[\mathbb{P}_1 = \frac{I_1}{I_1 + I_2}, \quad \mathbb{P}_2 = \frac{I_2}{I_1 + I_2}.\]Thus, in order to reach a given light, we have to traverse through its ancestors with a given probability each time. At each step in the traversal, we need to make sure the PDF of selecting our light is correct, so we use a pdf_factor to scale our PDF based on which direction we chose. For example, if we traversed in the order \(L_1, R_2, L_3\), then we also scale our pdf_factor by \(P_{L_1} \cdot P_{R_2} \cdot P_{L_3}\).

Finally, the last step is less related to the paper and more so to Blender’s code. Right now, Blender samples lights and emissive triangles by generating a distribution where each primitive’s totarea represents its relative weight of being selected. The distribution is “pre-baked” in the sense that it creates a 50-50 probability of selecting either a triangle or a light. Then the probability of selecting a triangle (given that a triangle was selected) is now proportional to its area, and there’s an even probability of selecting any light. Therefore, we have the following code:

// intern\cycles\scene\light.cpp

if (trianglearea > 0.0f) {

kintegrator->pdf_triangles = 1.0f / trianglearea;

if (num_lights)

kintegrator->pdf_triangles *= 0.5f;

}

if (num_lights) {

kintegrator->pdf_lights = 1.0f / num_lights;

if (trianglearea > 0.0f)

kintegrator->pdf_lights *= 0.5f;

}

Then the function light_sample() in the device kernel uses this PDF factor to scale the light sample’s PDF after the rest of the computation. In our case, we still want to use the light_sample() function, but this baked distribution is no longer being used in our sampling logic. The PDF is dynamic depending on the importance and we’re scaling it in our own sampling function, so we can’t use any pre-baked data. Instead, we just override the factors so that light_sample() doesn’t additionally scale our PDF incorrectly:

// intern\cycles\scene\light.cpp

if (scene->integrator->get_use_light_tree()) {

kintegrator->pdf_triangles = 1.0f;

kintegrator->pdf_lights = 1.0f;

}

else {

// code from above

}

If you’ve read the original paper, “Importance Sampling of Many Lights With Adaptive Tree Splitting” by Alejandro Conty Estevez and Christopher Kulla, or my previous post, you may also recall that there’s also something called the splitting threshold. This is when variance of the child nodes is too high, so we choose to sample from both the left and right child instead. However, this implementation isn’t very convenient in the context of how Cycles functions. Since we have to queue kernel tasks and integrate_surface_direct_light() expects to handle a single light at a time, we’d have to do some weird workarounds to implement the splitting threshold (which samples multiple lights at a time). For now, we’re putting this to the side, but we’ll re-examine it later when the implementation is more stable.

Debugging, Testing, and Benchmarking

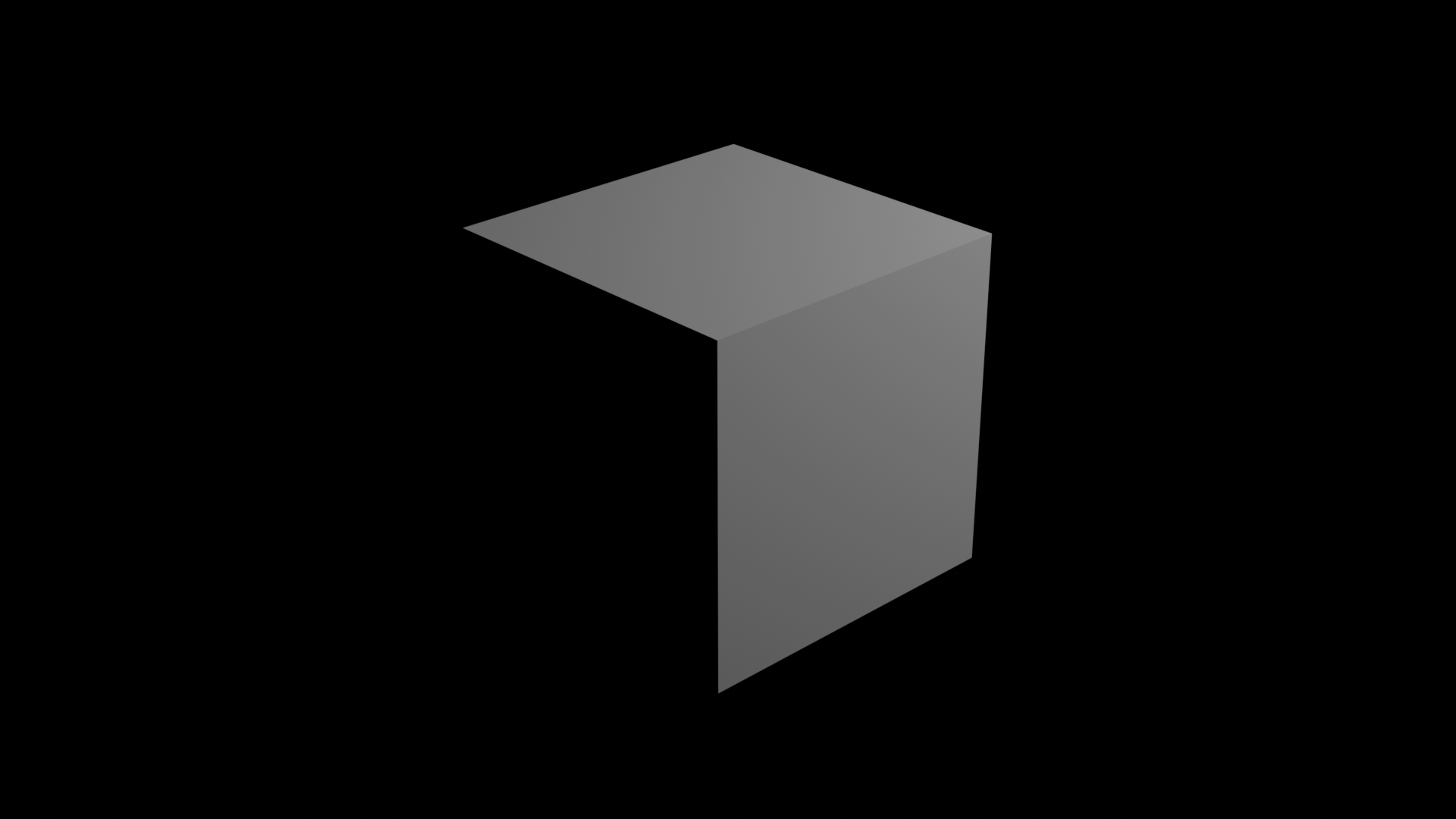

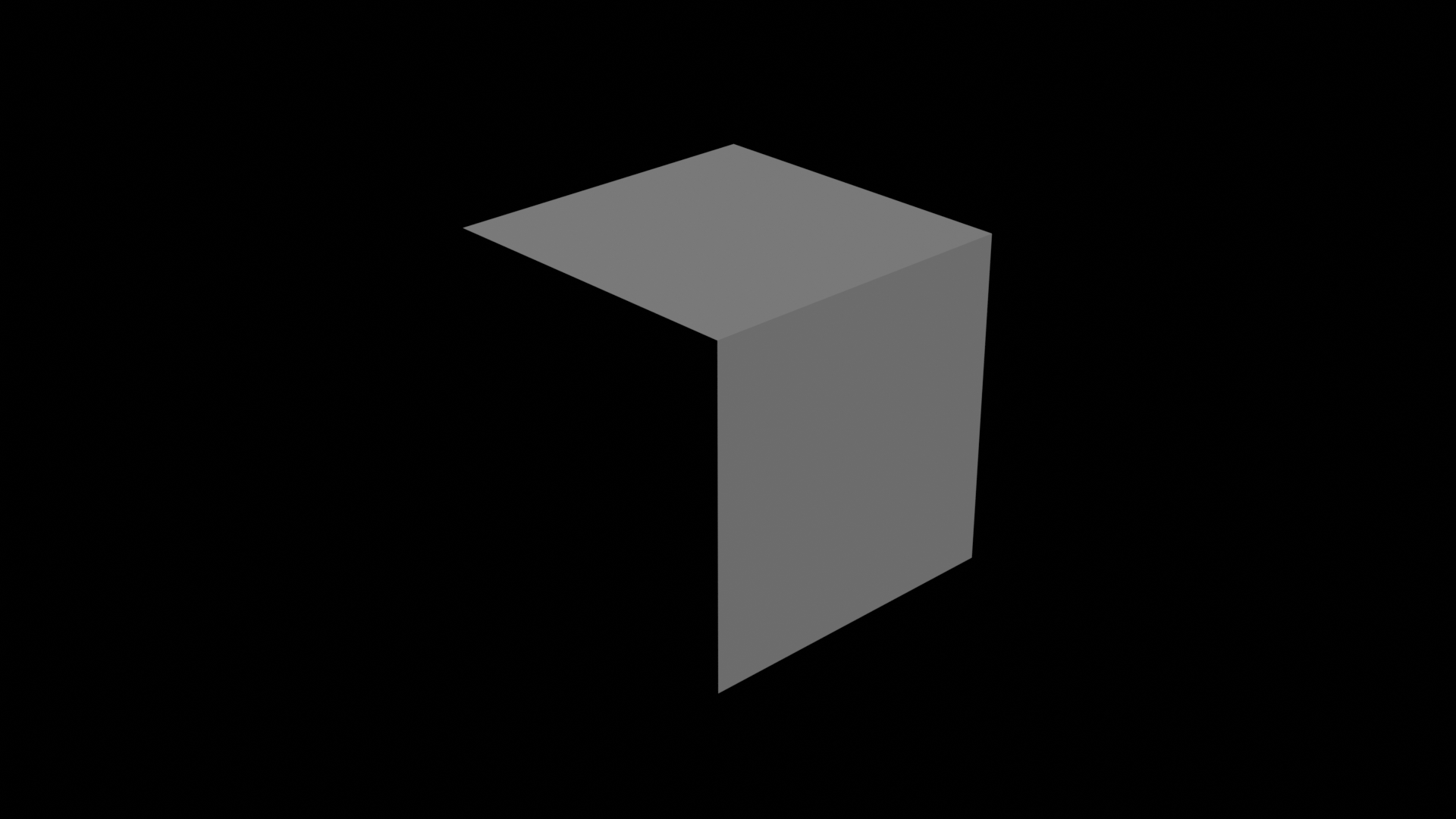

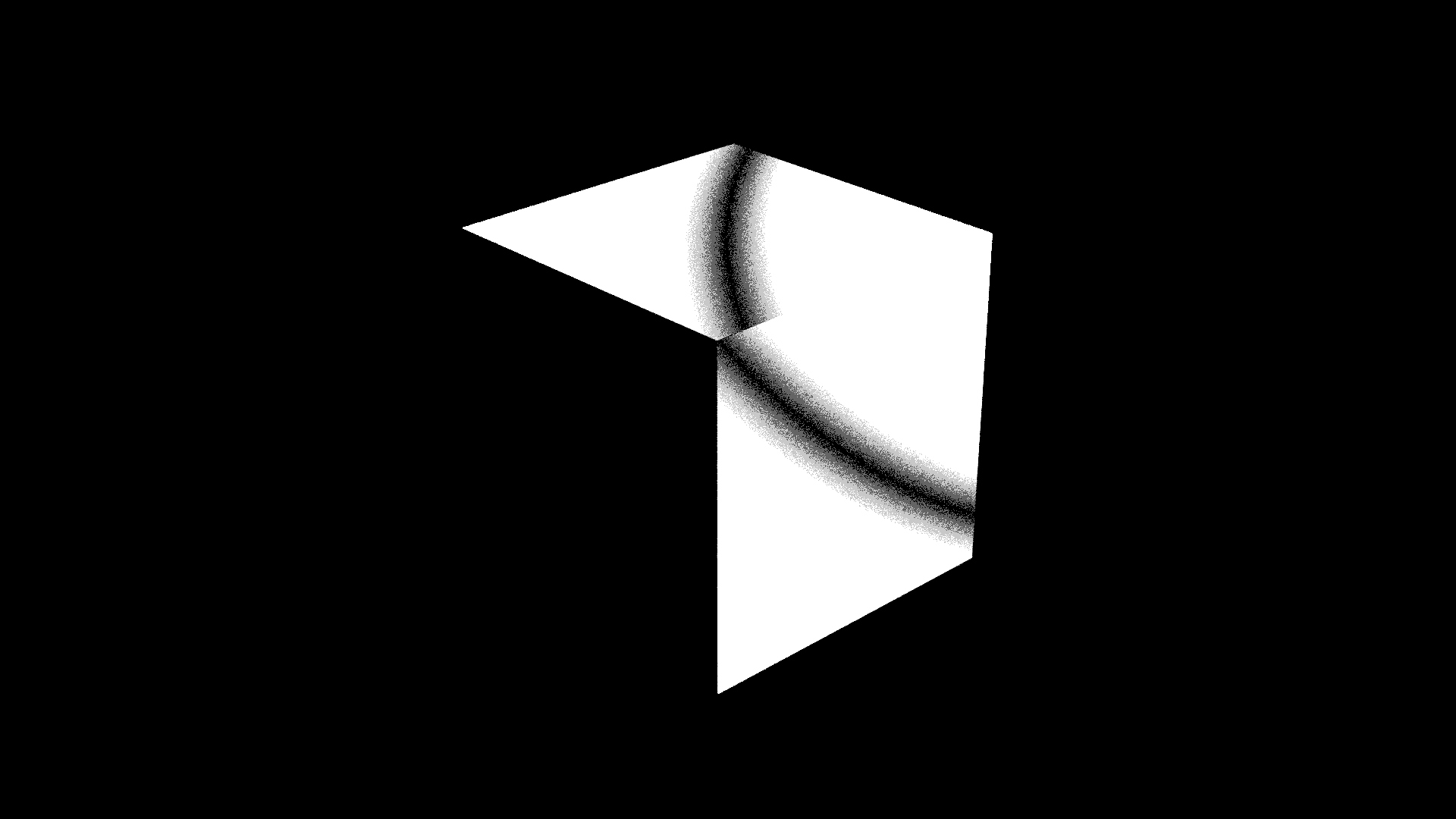

To debug and test this scene, I created a bunch of scenes that just had a bunch of point lights and no background light. To start, the goal was to get a single point light and cube rendering properly. LazyDodo pointed me towards a useful tool called idiff which can be used to compare 2 renders, which I would use to verify the accuracy of my implementation when compared to the default Cycles render. It also lets you output a difference image and scale the results (to make it easier to see), which was very useful. Lukas also recommended another tool, tev, to compare images, but I haven’t gotten the chance to try it out yet. Anyways, this is an example of why idiff is important; here are two of the first renders I did. With one point light, no background light, and a single cube, the left is the Cycles default implementation and the right is my new implementation:

Looks pretty similar, right? Maybe to the naked eye, but idiff shows the following when I scale the absolute difference by 100:

In reality, the right corner of my implementation is too dark while the other corners are too bright. There were actually a few things wrong with my first implementation. I accidentally swapped the normal and position arguments (this took an embarrasingly long time to figure out), and I didn’t account for the pre-baked light PDFs.

Other errors included:

- Forgetting to update the node’s energy when transferring it to the device

- Not initializing the bounding box and bounding cones properly when doing SAOH

- Forgetting to scale the random number used

- Swapping the values for \(\theta_i'\) and \(\theta'\) Last but certainly not least, this was the error that took me at least 7 hours to debug:

// intern\cycles\kernel\light\light_tree.h

if (tree_u < left_probability) {

knode = left;

index = index + 1;

tree_u = tree_u * (left_importance + right_importance) / left_importance;

*pdf_factor *= left_probability;

}

else {

knode = right;

index = knode->child_index;

tree_u = (tree_u * (left_importance + right_importance) - left_importance) /

right_importance;

*pdf_factor *= (1 - left_probability);

}

The error is in the else statement, where knode = right is called before index = knode->child_index. As a result, when we traverse to the node where child_index is set to the last index in the array, we’re now in an interior node but index is the last index possible. Then since knode is still at an interior node, we try to access the left child which is index + 1 and thus out of bounds.

I guess after a few hours of debugging already, I didn’t have it in me to catch this bug by inspection - I honestly wasn’t expecting this error at all. Since the conditional is probabilistic, I never encountered it when I was stepping through the code line-by-line. I was also running the render tests through a release-mode build where there were no assertions. I finally hit the assertion fail when I accidentally continued execution in my line-by-line debugging in a debug-mode build.

Now the implementation finally has some degree of accuracy when it comes to point lights (at least in special cases). In scenes with lots of point lights, there seems to be some more significant differences in the edges of the cubes. When I increase the sample size, the error there does still decrease, but at a slower rate than the rest of the render. This might be something I’ll look into again later, but I suspect that it’s mostly a precision thing, or something related to the normals near the edges of the cube.

Overall, debugging took me way longer than I’d like to admit, but in a sense, I guess it’s a necessary evil. I definitely learned a lot through it, and I hope that addressing these errors early on will make it easier when debugging further features.

Closing Thoughts

This was my first time really diving into Blender’s source code, so it was really rewarding when some of the tests started passing. That said, it’s still a little too early to start celebrating because these are just special test cases. There’s a lot more testing that needs to be done, and then after that, it’ll be time for optimizations too. As I mentioned in the devtalk, the rough timeline is as follows:

- Spot and area lights

- Emissive triangles

- Background and distant lights

- Volumes

- GPU Implementation

As for the immediate next steps it should be pretty easy to support spot lights and area lights. Since they’re just different lights, it should just be a matter of handling their orientation bounds appropriately. After that, emissive triangles are next on the list - this should also be relatively straight-forward to implement as long as the bounds are constructed properly.

As usual, please let me know if there are any errors in this post - I would love to better my understanding of things! If you have any questions or concerns, feel free to ask on the devtalk feedback thread. If you also have any scenes with a lot of lights, please do share them! I’ll try to test them as soon as it’s ready for testing.