NOTE: This branch has finally been merged into master (yay!). It seems like most of the work below was reverted due to its substantially larger overhead, but I’m leaving this post here because I still think it’s an interesting idea to explore.

As the algorithm has improved, we’ve found that the importance heuristic alone can only go so far. For example, here are some obvious artifacts in a test scene made by Alaska (special thanks for so much debugging help!):

Here, that dark region is where the importance heuristic thinks that the area light will be a heavy contributor, but it’s actually cutoff already. It’s especially extreme at low samples, but just in general, it’s something we need to fix.

The original paper doesn’t really discuss any issues of this nature, but it does heavily emphasize that the adaptive splitting is an essential part of their work. The point of adaptive spltting is that sometimes, the light tree node’s variance is pretty high, so it’s safer to just sample from both the left and right child in those cases. However, the caveat here is that Cycles is structured such that the direct light sampling is expected to use a single light at a time, so we can’t exactly just continue adding samples.

Potential Solutions

Resampled Importance Sampling

The first proposed solution was to implement resampled importance sampling (RIS). This is a topic that I’ve only briefly skimmed over so far, and also not our final solution, so I’ll keep this section brief. The general idea is that we’ll do the adaptive splitting, but we keep track of all the samples in a list. Once we’ve populated our list, we can use a more refined computation (e.g. computing an actual LightSample) to weight each entry when we’re choosing our final sample. This method kind of allows us to consider the proposed samples from adaptive splitting, and would be especially useful in cases like above where the original importance heuristic is off.

There’s a bit of nuance related to the functions used, the target distribution, and the size of the list. I’m not really going to get into the details here, but if you’re interested, the paper I referenced was “Importance Resampling for Global Illumination” by Justin Talbot. In any case, the downside to this approach is that it generally assumes a fixed list size. However, we never really know how many adaptive splitting samples we’ll be getting, and it’s not the best in terms of memory usage either. It also means we’ll have to do another pass through the list once we’re done traversing the tree.

Weighted Reservoir Sampling

Fortunately, I happened to come across another technique called “weighted reservoir sampling” while I was looking into NVIDIA’s ReSTIR algorithm. It also just so happens that there’s a chapter about it in RTGII. It’s actually able to select a reservoir with an arbitrary number of samples, but we’re only concerned with the special case where here. The idea of this technique is actually pretty simple, and kinda similar to the first technique. The main difference is that we’re selecting a single sample out of an arbitrary stream of samples.

So for our case, think of our light tree traversal with adaptive splitting. When we hit our first sample, we hold onto it with probability . Here we compute the weights using some slightly better heuristics, such as actually taking a LightSample. Then, assuming that our traversal has split a few times, we’ll eventually encounter another candidate sample. Now we hold on to second sample with probability , and otherwise we stick with our current sample. We continue this process until we complete traversal or whatnot.

After samples, the probability of selecting the -th sample is:

There are a few big advantages to this approach, when our reservoir is size :

- The memory usage is much better because we only need to keep track of the currently selected light and the accumulated weight of the samples;

- The algorithm works with a stream of samples, so we don’t need to worry about the specific number of adaptive splitting samples, and we can also compute it while we’re traversing the light tree.

PDF Considerations

Overall, the weighted reservoir sampling seems like a great solution for adaptive splitting, but the elephant in the room is how to properly calculate PDFs now. In this section, I’ll describe what we can do to keep our estimator unbiased.

Direct Light Sampling

So ignoring multiple importance sampling for now, let’s assume that we’re trying to approximate the following integral:

In this case, our standard Monte Carlo estimator looks like the following:

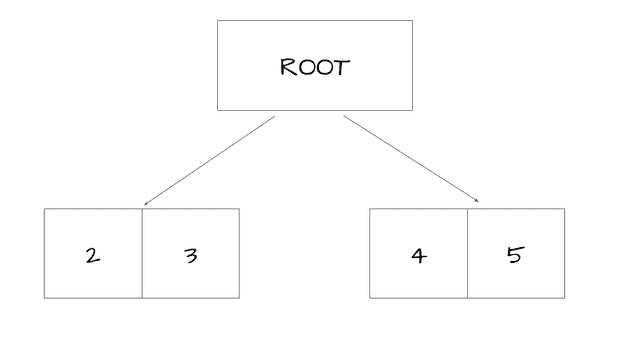

However, in the case of weighted reservoir sampling, calculating the true probability of selecting is pretty tricky. This is because the stream of candidates varies based on how we traverse the light tree, which in turn affects the weights. As a simple example, suppose we have the following tree where we split at the root:

The values are used as the relative weights, e.g. there’s a probability of selecting from the left child. Since we’ve split, we select an element from both children, and then compare the two elements again. Let be the random variables representing the left and right child respectively, and be the final sample. Then we have:

The values are used as the relative weights, e.g. there’s a probability of selecting from the left child. Since we’ve split, we select an element from both children, and then compare the two elements again. Let be the random variables representing the left and right child respectively, and be the final sample. Then we have:

The main idea is that this computation, even for this simple example, can be quite complicated. However, the proposed solution is to adjust our estimator such that is equal to the probability of including as a candidate sample times the probability of selecting as our final sample.

I’m still having some difficulty formalizing this, but consider the use of this estimator for the case of . There are two cases where is selected as our final sample, with the corresponding probabilities:

- 2 is selected from the left () and 4 is selected from the right ()

- 2 is selected out of the list ()

- 2 is selected from the left () and 5 is selected from the right ()

- 2 is selected out of the list ()

Intuitively speaking, if we look at the specific case for , we would have the following frequencies:

This should extend to the other values, which would imply that our estimator remains unbiased. This should always work because we guarantee the invariant:

where is the total number of lists containing some sample and is the probability that the rest of the list is constructed. Furthermore, my guess is that this will extend cleanly to the continuous case, although this is also where I’m having some trouble formalizing things.

Closing Thoughts

As mentioned at the top, there were a few reasons why this idea didn’t pan out:

- It was hard to convince that this estimator would remain unbiased;

- Regardless of if it remained or not, each sample was taking too much time to compute.

But it was a really interesting idea! I also got to talk more about it with Chris Wyman (really cool person at NVIDIA who wrote a chapter about Weighted Reservoir Sampling in Raytracing Gems II) at SIGGRAPH 2022. That might deserve a post of its own, but the TLDR is that I volunteered there, met a lot of cool people, including Ron Roosendaal himself, and had lots of fun!